Throughout Scottish history, there are few documented individuals who pushed the boundaries of gender as early as Dr James Barry.

Originally born in Cork, Ireland, the story of Barry and how he managed to disguise his born-identity during his time in Edinburgh and throughout his life, is a remarkable tale.

Born Margaret Ann Bulkley, and assigned female at birth, Barry was described as an intelligent child. From the little information available, it is likely that Barry was born sometime in 1789 to Jeremiah and Mary-Ann Bulkley. The year of Barry’s birth is often disputed and argued due to the fact he lied about his age later on in life. His knowledge and natural intelligence was clear from an early age, however, Barry and his family were all too aware of the hurdles in place for women in formal education.

Mary-Ann Bulkley’s brother, and later inspiration for her family’s plot, James Barry, was a celebrated artist and professor. This uncle went on to influence Barry’s path and pursuit of education, alongside some liberal minded friends. Upon the death of Barry’s uncle, his mother and friends conceived a plan that would allow the young Margaret to study medicine. Margaret was to present as the nephew of James Barry, his recently-deceased uncle and name-sake. Barry’s academic associates decided to enrol him in the University of Edinburgh, so in 1809 the new James Barry and his mother, Mary-Ann, boarded a small fishing boat and made their way over to Scotland where Barry enrolled as a medical student.

Barry wore insoles in his shoes to appear taller and larger garments such as overcoats, whenever he could to obscure his figure. While there were suspicions around his character, the doubts from his peers were rooted in his age and not his gender. Many believed he was still a young boy and had lied about his age to get into medical school. Due to this, the University Senate actually tried to postpone Barry’s final exam. Luckily, one of Barry’s close patrons, the Earl of Buchan, managed to persuade them otherwise. He went on to pass his final exam and receive his degree in 1812.

Barry moved from Edinburgh to London, where he practiced medicine at The United Hospitals of Guy’s and St Thomas’. He then applied to the army to be an assistant surgeon. Due to Barry’s more feminine features he had to lie on his application, claiming to be 18 years old. In reality, he was 24. Barry passed the exam from the Royal College of Surgeons and was successful in his application. In 1815 Barry was promoted to assistant staff surgeon and because of his supposed young age, was thought to be a prodigy. After completing his military training, Barry was posted in Cape Town, South Africa. After months at sea, Barry successfully arrived in Cape Town leaving the crew and passengers none the wiser. Barry spent the next 10 years in Cape Town.

Thanks to his trusty connections, Barry was able to introduce himself to the governor of the colony in Cape Town, Lord Charles Henry Somerset. Somerset and Barry became well acquainted, he was even called upon when Somerset’s daughter fell ill and saved her life. Barry became very close with the family and was even appointed as Somerset’s personal physician. He was also appointed Colonial Medical Inspector by Somerset. The two were so close, many historians speculate whether Somerset knew Barry’s secret, though it was never proven. In 1824, rumours spread in Cape Town that Barry and Charles were involved in a romantic relationship. Not only was homosexuality illegal at this time, but worse consequences were faced for those within the army. Barry and Charles were investigated but eventually exonerated due to a lack of evidence. The true nature of their relationship is still unknown to this day.

Somerset was called to England to answer for the actions of his administration, most likely fuelled by the allegations of homosexuality. Barry lost his dear friend, and also the only person able to mend his often burned bridges, which were the common result of his hot temper and tendency to speak out against the local authorities. After Somerset’s departure, the Office of the Colonial Medical Inspector was abolished and Barry was forced to resign and continue to practice medicine privately. This led to one of Barry's most celebrated accomplishments. He was called to the home of a woman who was unable to give birth naturally. Barry successfully performed the cesarean operation and both mother and baby survived. The child was even named after him, James Barry Munnik. This is one of the first known cesareans that didn’t result in death of either mother and child, with only three recorded cases prior to Barry’s successful surgery.

Throughout Barry’s time in Cape Town he improved the living conditions of the Cape colony and spoke out about the poor sanitation and water system. After a decade of work, Barry received word in 1828, that his dear friend Charles Somerset was dying due to complications of heart failure. Without hesitation, Barry left his post in Mauritius to return to England and treat Somerset. Barry worked tirelessly to care for Somerset, however, after two months of treatment, Somerset passed away.

After Somerset’s death, Barry’s life consisted of postings throughout the British empire, including Jamaica and the remote island, St Helena. In 1846, Barry contracted yellow fever while working in Trinidad. Allegedly, the two physicians treating him had uncovered his secret, but decided to keep quiet. Once recovered, Barry travelled once more. Notably, he helped in Crimea during the height of the war, where he continued to fight for better hygiene. He even scolded the famous Florence Nightingale!

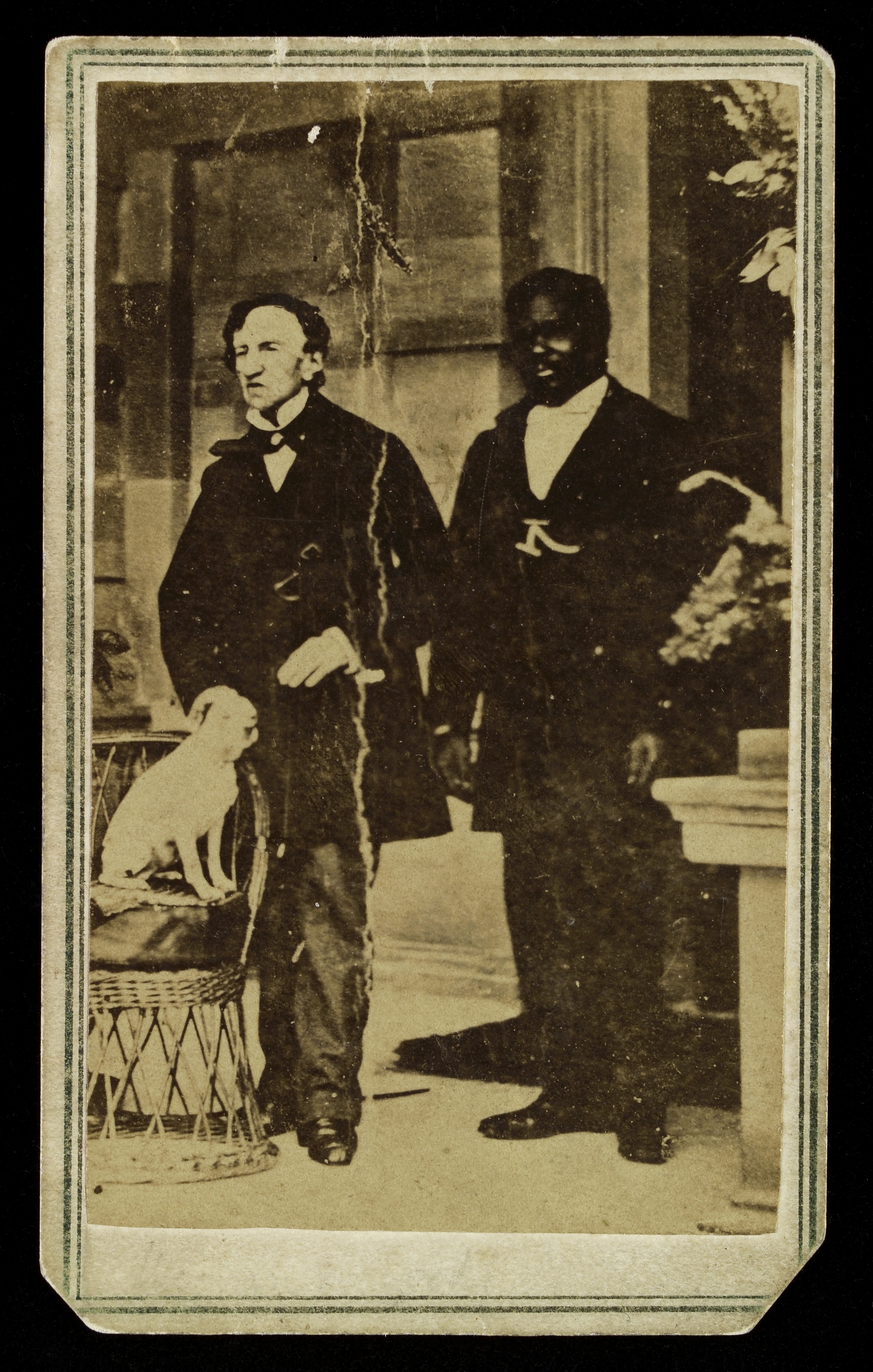

Left Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Barry’s final posting was in Montreal in Canada, 1857. There he was Inspector General of hospitals where he avidly fought for the health and living standards of minority communities. Due to Barry’s temper and frequent squabbles with people in high places, the health board in England forcibly retired him due to ill health and old age. Barry spent the rest of his life revisiting many of the colonies he had worked in during his postings and then residing in London until eventually passing away due to dysentery on the 25th of July 1865 at the age of 76. Barry had left strict instructions in the event of his death to discourage anyone to inspect his body and thus reveal his secret. He asked to be buried in his bedsheets without further examination of his corpse. However, his wish was ignored. The woman who prepared Barry’s body discovered his sex assigned at birth. It is alleged that when Barry’s physician refused to pay the woman, she revealed Barry’s secret to the press. In a letter by the physician, Dr McKinnon wrote, rather liberally for its time, “It was none of my business whether Dr Barry was a male or a female, I thought he might be neither.” Once the news hit the public, many came forward and claimed they had known all along. The British army responded by attempting to conceal Barry’s documents, hoping to suppress the story.

James Barry was buried with full military rank in North West London. He was a skilled doctor and activist for better hygiene and living conditions, including improved sanitation, for those less fortunate. He is definitely worthy of LGBT+ icon status, and will continue to be a celebrated University of Edinburgh alumni.